Pathways to Information: Accessing Knowledge by Leveraging Language (Part 1)

The knowledge-building vs. strategies debate, misinterpreted due to messy messaging, needs to find a direct route from decoding words to a deep understanding of text. Some suggestions in four parts.

Part 1: Types of Knowledge

Freedom and Constraint: Even now after several decades I can see the look of frustration on the face of a colleague rattled by a challenging lesson with his algebra students. He stopped me in the breezeway for a moment of lamentation, concluding that the teaching profession simply doesn’t accommodate your "average" teacher. If he was right, then we've got a big problem since most of us are average. Or, as Robert Pondiscio recently remarked:

Teaching can't be for saints and superstars only. There aren't enough of them to go around.

The point is that expectations for teachers are often way too high and accommodations to help them succeed far too few.

I remember another colleague in my English department asking me about a lesson I had taught that she wanted to use, and she spent her entire prep period peppering me with questions like, what did you say first, then what did you say, and after that, etc., scribbling down every single word I said. This teacher required a script, and I used recollection—and improvisation—to provide her with one because I had no record of exactly what it was that I did in fact say during that lesson on that day since some lessons simply don’t lend themselves to being scripted.

I often think about this colleague when I hear knowledge-building advocates extol the virtues of the class discussion. While there is unquestionably much to value in this activity, I believe having a meaningful discussion with a class can fall into the category of the elusive, unscripted lesson, sometimes leaving your average teacher feeling inadequate when it comes to knowing what to say or do next.

There’s a term for this strategic knowledge—contingent scaffolding—which simply means that your next teacher move is contingent upon a student move. It’s not four-dimensional chess; it’s just everyday teaching to three-dimensional children. Depending on questions students are asking, or how they answer one of your questions, you may need to alter the trajectory of the lesson and take it in a new direction—or simply revisit prior instruction to reteach what hasn’t been completely understood.

In a recent discussion on the Better Teaching: Only Stuff That Works podcast, Carl Hendrick (How Learning Happens) refers to the observation of a pro-level soccer player, who explains that all the players at that level have comparable skill; the difference is that the most effective ones make better decisions.

Hendrick applies this analogy to teaching. While struggling to make better day-to-day decisions, teachers often fall victim to insufficient information from feedback loops. In sports—and certainty in chess—he asserts, if you make a mistake, you get instant feedback. The loops are really short, and bad decisions are punished quickly, and you see what you did wrong. But with teaching the feedback loops are long—so long, in fact, that:

You might not find out that you did something wrong for six months, or even longer—or ever!

The podcast also discusses the tension between a student’s cognitive constraints and a teacher’s instructional freedom. This is where research from the science of learning can provide the necessary restrictions on a teacher’s lesson-planning freedom to help them make better decisions based upon a number of factors, including the knowledge of the limitations of working memory (cognitive load theory), what John Sweller (Efficiency in Learning) calls cognitive architecture.

Successfully navigating the tension between the constraints on a student’s capacity to learn and the freedom a teacher has to design a myriad of lessons in a variety of ways is what Hendrick calls great teaching. Simply speaking, we need to put teachers in a position where they are equipped to make decisions that lead to better outcomes for their students. This is why scripted programs can be beneficial for new teachers.

Zach Groshell (Just Tell Them) reminds us:

Children thrive in environments where the teacher has high expectations, clear directions, deep subject knowledge, brisk pacing, and involves all students through continuous interactive teaching and assessment. This is also achievable, but schools have to commit to it!

So what's our backup plan if schools don't commit to establishing this environment? This is why simple instructional practices like having a ‘script’ generated by students in the form of a written response to a question, a completed graphic organizer, or a summary paragraph—something simply written down—can be beneficial to both teacher and student, providing sign-posts for the teacher’s spontaneous decision-making and involving all students through continuous interactive teaching. Specifically, for the student, it anchors thought by pinning it to paper or a white board. For the teacher, it can provide a structure that might be missing from the transient nature of a whole-class discussion where the teacher is orchestrating all the moves.

The question is: What can help structure a teacher’s train of thought when there’s no one around to press recording in progress? That's what well-developed strategy instruction can provide—a record of student thought made visible for reference and redirection—and timely reminders to the teacher to move on or go back and reteach if it’s evident that there was a breakdown in comprehension. Moreover, if we base this strategy instruction on research supporting both teaching and learning, we can impact how well our students comprehend what they read.

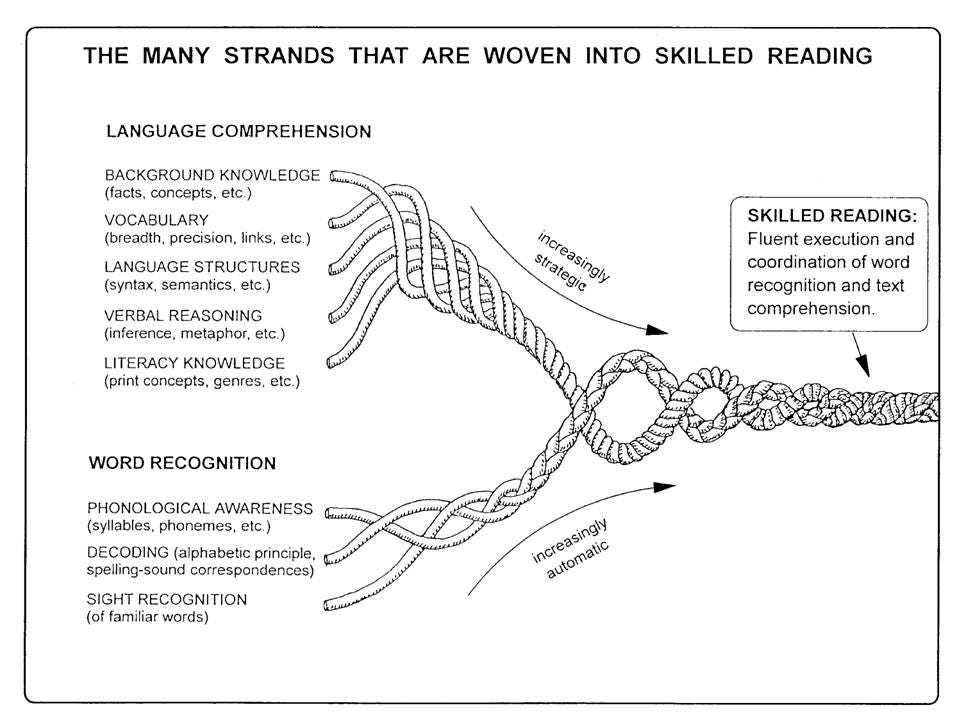

Strategic Knowledge: The Role for Remembering: In Types and Qualities of Knowledge (1996), the authors present four types of knowledge necessary for problem-solving in science: situational, conceptual, procedural, and strategic. Although not commonly considered problem solving, understanding grade-level text most definitely poses a problem for many students, especially in elementary school, because even if they are familiar with the content, there can be academic vocabulary and complex sentence structures that confound their capacity to comprehend what they read by impeding their ability to make the appropriate connections and inferences—the verbal reasoning part of Scarborough’s Reading Rope.

This is where strategic knowledge can be helpful:

Strategic knowledge helps students organize their problem-solving process by directing which stages they should go through to reach a solution. A strategy can be seen as a general plan of action in which the sequence of solution activities is laid down (Posner & McLeod, 1982). Elements of knowledge belonging to the first three types are specific, applicable to certain types of problems in a domain, whereas the last type, strategic knowledge, is applicable to a wider variety of types of problems within a domain.

How does this application of strategic knowledge translate into the elementary school classroom? Students are presented with a complex, grade-level text with the goal of having them understand it and retain the knowledge it contains. To do this, they need a general plan of action that helps them organize and analyze what they are reading in order to be able to synthesize a response to it. How we provide this plan of action matters.

Carl Hendrick explains the importance of teaching with the goal of remembering:

A really important question; how often do students need to encounter something to remember it? Basically it's not so much the amount of times you retrieve something as the ways in which you retrieve it. So what we want is not so much rote repetition 3 times (although this has its place for certain things) so much as a kind of variation in how students retrieve knowledge. We want students to have to retrieve something in a range of different ways, across a range of different times and to apply it in a range of new ways.

Can we call this need to help students retrieve something in a range of different ways an important consideration for the classroom teacher, one that provides the constraints on lesson planning that are necessary to assist in making better instructional decisions? Hendrick emphasizes the importance of structuring learning so that information is revisited through different modalities and contexts. He states:

There is a broad consensus that varied retrieval practice enhances long-term retention significantly more than simple repetition or rereading. When students encounter material through different modalities and contexts, they develop multiple retrieval pathways to access that information.

Has Carl Hendrick solved our strategies vs. knowledge-building binary by explaining the pathway to retaining the knowledge we build, one that relies on effective instruction using different modalities and contexts? Can well-structured strategy instruction help create a plan of action and promote problem-solving by providing students with the paving stones necessary for the retrieval pathways that allow them to access information?

Comprehension relies on knowledge, which is expressed through language—through the vocabulary and sentence structures nestled within paragraphs. Therefore, unlocking the vocabulary, syntax, and paragraph structure (and the relationships between all of these literacy components) of what is read—releases that knowledge (extracting) to be used in contexts beyond any particular piece read (constructing). That is how I've broadened Catherine Snow's definition of comprehension from Reading for Understanding: Toward an R & D Program for Reading Comprehension (2002), where she tells us that comprehension involves:

the process of simultaneously extracting and constructing meaning through interaction and involvement with written language.

Going forward, these are the moving parts we need to pin down:

How do we help teachers make better decisions and realize when they haven’t made good ones?

How can promoting strategic knowledge support students in remembering content knowledge?

What is the relationship between content knowledge and the language structures that express it?

What kind of action plans are effective in tackling knowledge-building text?

In Part II, Tricks of the Trade–or the Trade Itself, we’ll take a close look at Daniel Willingham’s view that reading strategies are a “bag of tricks”. In addition, we’ll look at the importance of the “decoding threshold” as well as the inextricable relationship between knowledge and language, how each of these plays a crucial role in comprehension, and how scaffolded strategy instruction can support comprehension by promoting language development.

Always striving to make sense—please let me know when I fail.

I agree with Mike--this is a great piece! Another piece I would like to explore is how do schools account for teachers at different places and different levels. If I were teaching high school math, you better believe I would want a script and I know that well organized script could help me be a good math teacher even though I would not ever be a superstar. On the other hand, if I were teaching first grade literacy I would want the ability to be able to pull things together and use my thirty years of experience and success. It's. a question I have been sitting with over the past few years. I know there is no easy answer but I will keep exploring it.

Great piece, Harriett. Thank you. If I had one wish for every teacher, superstars and average Joe's alike, it would be that they find themselves surrounded by colleagues and a school that has firmly committed to a common teaching and learning environment, where they all use the same terminology, and commit to learning from each other. Thanks again.