If I Had One Wish

Something snapped inside me last week during a perfectly ordinary reading lesson with six second-grade intervention students from a dual language immersion (DLI) class. I watched and listened as one student patiently applied everything I had taught her to navigate three different pronunciations for ‘ea’ in the title of a story about inventions: Dreaming of Great Ideas.

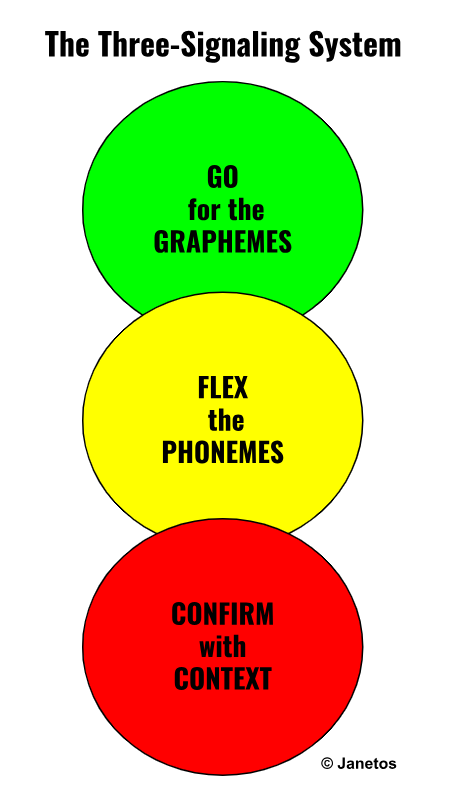

There was only one path forward because these words were in the table of contents with neither picture support nor context to distract her from attempting to decode each one. In succession, she grappled with the graphemes and applied flexible pronunciations to change the phonemes to arrive at her destination: a known word. It all went according to plan.

Something snapped because I realized this was a perfect illustration of how senseless the circuitous route to reading instruction promoted by Whole Language and Balanced Literacy advocates can sometimes be (examples to follow). It can waste time, to be sure, but more importantly, it can crowd out more effective and efficient methods that might never gain purchase if they are not prioritized. If the pursuit of efficient decoding doesn’t dominate reading instruction, then orthographic mapping—the ability to store words that have been decoded by connecting spellings to sounds and meaning—won’t develop, which is required for automatic and accurate word recognition.

The fourth of Reid Lyon’s ten maxims states:

All good readers are good decoders. Decoding should be taught until children can accurately and independently read new words. Decoding depends on phonemic awareness: a child’s ability to identify individual speech sounds. Decoding is the on-ramp for word recognition.

The tenacity my student showed reminds me of a Saturday Night Live skit where Steve Martin is comfortably seated on a festive set and affably expressing his holiday wish:

If I had one wish I could wish this holiday season, it would be that all the children in the world would join hands and sing together in the spirit of harmony and peace.

If he had a second wish, he goes on to say, it would be for thirty million dollars to be given to him each month, tax free, in a Swiss bank account. You can imagine how swiftly his original heartfelt wish is cast aside in this exhortation as his selfish desires accumulate, until the cr** about the kids becomes a perfunctory afterthought inserted in an offhand manner.

Well, I want to talk about the kids—and keep talking about the kids—and never stop talking about the kids. If I had one wish:

It would be that all the reading influencers in the world would join hands and sing together in the spirt of science and sanity about the necessity of centering foundational skills instruction on facilitating orthographic mapping.

If we could just come together and agree on this one single thing—what readers do when they encounter new words and why they need to do it—it would make a big difference to our students. I’m calling this process graphophonemicsemanticalizing—not because it rolls off the tongue, but to demonstrate that you had to stop and slowly sound out (decode) that word because it is new and has not been orthographically mapped to your memory for future retrieval.

On a recent podcast Carl Hendrick (How Learning Happens) states:

If you’re not explicit about what you want kids to know, and what you want them to do with that knowledge, then you’re widening the gaps.

Here’s what I want kids to know: how graphemes and phonemes work in words.

Here’s what I want them to do with that grapheme-phoneme knowledge: apply it to decode unknown words to facilitate orthographic mapping.

Everything, Everywhere, All at Once

I choose this one wish for our collective kumbaya because if this approach to word identification is accepted, instructional methods (including cueing charts) for developing foundational skills should logically fall in line.

Here’s a common lament in stories told by Balanced Literacy advocates:

Woe is us! We have been dealt a bad hand with this darn English language (ask Mark Twain) which is impossible to decipher. So there’s really no way to deal with it except by making reading instruction every bit as cumbersome and convoluted as the language itself.

It’s like the principle behind homeopathy: treat like with like. Treat food poisoning by ingesting arsenic (arsenicum album); teach an opaque English language with cueing charts prompting procedures that are equally opaque. One Whole Language proponent recently referred to some of the principles of Structured Literacy as kooky talk. Well—back atcha, buddy!

Something snapped last week because even more than ever before I could clearly see what is kooky about so many of the stories we’ve been told and sold. Fifteen years working as a reading specialist with hundreds of struggling readers has made it clear to me that we have been subjected, and continue to be subjected, to instructional gaslighting. Any attempt to rely on the research that points to a straightforward path to word recognition by simply teaching students to segment phonemes and blend graphemes so they can encode and decode words to facilitate orthographic mapping is often met with some version of this story:

Of course there’s no simple way to teach word recognition! The English language is far too complicated for a simple approach, and since every child learns differently, we’re stuck between a rock and a hard place. Look at all these various spellings for a single sound! You are a fool, and it is foolhardy to think that working on the word level will help students read books because those books have way too many words that are difficult to decode. And don’t forget: it’s overall meaning that really matters, not individual words.

Dreaming of Great Ideas

Linnea Ehri has a wonderful anecdote from the mid-70’s about sitting in a lecture by Ken Goodman, the father of Whole Language, and finding herself disagreeing with his explanation of the reading process. In this Reading League podcast (at 19:00), she recounts how he presented his position at an institute she was attending, a theory proposing that reading is a psycholinguistic guessing game whereby readers are sampling cues to guess words. Later, Ehri submitted a paper responding to Goodman’s lecture by addressing his claims. She states:

Having my background in psycholinguistics, I was certainly sympathetic to the idea that readers hold certain syntactic and semantic expectations about upcoming words in the text. However, I wasn't convinced that that is how readers read most of the words in text.

Ken Goodman’s mistake was messing with Linnea Ehri by returning her paper with ‘comments’ that were a parade of negatives—actually one negative—NO—in the margins along with a final statement:

Reading is not a process of recognizing words.

Undeterred—in fact, even more motivated—she went on to research how reading is precisely that: a process of recognizing words. And when the paper she submitted to Reading Research Quarterly was similarly rejected with the following dismissive language, she was even more determined to press on. The editors wrote:

A worthless study that adds to the abundant confusion about learning words. This study signifies nothing but adds shear weight to the unwarranted focus on words. Really! When will we get to real issues? When will we try to look at kids reading real language? And when will we lift our eyes from the word to meaning?

That last sentence is so telling! Note the predicament we’re in:

Because we’ve lifted our eyes away from the word instead of keeping them laser-focused on it to help students use their own eyes to lift words off the page, we’ve failed to recognize what word recognition entails.

In the audio documentary At a Loss for Words, Emily Hanford interviews Ken Goodman where he proclaims: My science is different. Is this even a thing—choosing your own science?

Well—nobody—not Ken Goodman nor the editors of Reading Research Quarterly—can gaslight Linnea Ehri. Rejecting her theory and telling her that her science is not their science—just made her more determined to prove her theory of orthographic mapping until it became generally accepted as an explanation for how we store words in memory. If we accept this theory, we acknowledge the importance of teaching students to facilitate this word recognition process—pure and simple. Moral of the story:

Don’t ever gaslight Linnea Ehri because she will spend her entire career proving you wrong.

In fact, we are in If You Give a Mouse a Cookie territory:

If you give Linnea Ehri a lecture by Ken Goodman, she’ll listen attentively and take copious notes.

If she hears anything that doesn’t make sense, she’ll write him a paper explaining her own theory.

If Ken Goodman rejects her theory, she’ll conduct a study to support it.

If the editors of Reading Research Quarterly reject AND ridicule her study, she’ll persevere and conduct more studies.

If teachers successfully apply her theory, she’ll know she was right all along.

Clueless Cues

It won't surprise you that most teachers don't have time to access research, but those of us who do can reduce reading research to a game of doubles tennis that positions Ken Goodman/Marie Clay on one side of the net and Linnea Ehri/David Share on the other side. Just watch a few sets and then apply the recommendations of each pair to very quickly have everything you need to make daily decisions for your students that are both efficient and effective. It doesn’t take long to see which recommendations make more sense in a classroom context.

Here’s an example of the unforced error related to reading recommendations. Way back in 1967, Jeanne Chall wrote about the importance of code-based instruction to develop decoding skills in Learning to Read: The Great Debate. From Wikipedia:

She believed in the importance of direct, systematic instruction in reading in spite of other reading trends throughout her career . . . Her conclusions about the best way to approach beginning reading were unpopular when she first presented them, though they have subsequently gained acceptance in the literacy community.

Unfortunately, the psycholinguistic guessing game set in motion by Ken Goodman in the same year, endorsed by Marie Clay, and disseminated by Whole Language and Balanced Literacy proponents throughout following decades, still impacts reading instruction. Ken Goodman was challenged by Linnea Ehri in the 70’s, paralleled her career for the rest of his life, and published his final book in 2016: five decades devoid of self-doubt while flush with influence.

For example, the cueing chart below was featured in the 2020 article Using Context as an Assist in Word Solving. In fairness to the authors, they explicitly acknowledge and explain the importance of orthographic mapping:

Theory and research related to literacy acquisition have demonstrated, for decades, the value of helping learners develop skill with phonological/phonemic analysis and phonics skills (e.g., National Early Literacy Panel, 2008; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000) and have described the use of contextual information to direct and check their initial decoding attempts (e.g., Ehri, 2005, 2014; Share, 1995). Accurate word identification enables the orthographic mapping that enables word learning (Ehri, 2014) and occurs as readers form connections between written and spoken units in the course of reading words. These connections are bonded with the meanings of the specific words in memory and enable readers to recognize the words at sight—accurately and automatically, in isolation or in context.

However, having acknowledged this very important fundamental process, they then proceed to undermine their own assertions by presenting this mishmash of reading cues. Let’s apply them to reading the title Dreaming of Great Ideas.

1) Bad luck. No pictures in the table of contents.

2) To think about the sounds, you have to look at the letters that represent them.

3) Not enough information for sense-making for these challenging words.

4) Why do I have to meet my new beau’s parents (the ‘eam’ family) when I haven’t even gotten to know him (‘ea’) very well. And—alas—the ‘eat’ and ‘eas’ families are stubbornly anti-social in the two words they occupy, so no help at all!

5) Okay–I’ve read past the puzzling word to the next two puzzling words. Now what?

6) Right–I’ve gone back to the beginning.

7) Hmmm: Try Different pronunciations. There’s an idea—and it only took seven prompts to get here!

8) I can break the word into as many parts as it comes in, but those letters—Horace Mann’s skeleton-shaped, bloodless, ghostly apparitions—are still menacingly staring at me.

This is what I mean by gaslighting: giving me stuff that doesn’t make sense and then daring me to deny it’s helpful.

This kind of instructional disconnect is what drives teachers (this teacher) to declare:

STOP—JUST STOP. You’re making this all up, and you know what: it doesn’t help me or my students. I can’t see through the fog of your graphics, and my students need a straightforward path to processing letters and sounds. What you’re giving me just wastes everyone’s time. ENOUGH ALREADY.

Think about it: Dreaming of Great Ideas is a title. Without decoding these words, the reader doesn’t have anywhere else to go. Leading from behind may work in some organizations, but reading from behind doesn’t work in developing word recognition. Not only is it too taxing to just keep backfilling unknown words as context accumulates, but more importantly, a failure to decode by connecting spellings with sounds and meaning means the words are denied the opportunity to become orthographically mapped and available for automatic recognition the next time they appear. This point is important:

The goal isn’t just to get through the words on the page in any way possible and live to tell the tale. The goal is to get through the words and add those words to your lexicon so that the next encounter with them becomes that much easier.

Some people live like there’s no tomorrow. Well, not attending to decoding words in text is reading like there’s no tomorrow. As Reid Lyon said, decoding is the on-ramp for word recognition. Let’s say it one more time for the Balanced Literacy folks in the back row: DECODING IS THE ON-RAMP FOR WORD RECOGNITION. The graphemes and phonemes must be addressed in order to facilitate orthographic mapping so that they become automatically available to the reader. And the sooner the better.

No Boughing to Pressure

Here are the beginning lines to the poem The Chaos:

I take it you already know

Of tough and bough and cough and dough?

Others may stumble, but not you,

On hiccough, thorough, lough and through?

Listen to Ricky Ricardo attempting to read the words bough, rough, through, and cough. Instead of throwing up your hands\in despair, just be aware that the English language requires flexible pronunciations. Face it. And then get over it.

Satirist, singer/song-writer—and Harvard mathematician—Tom Lehrer (Hooray for New Math!) quipped that many books and movies are about people who spend a lot of time bemoaning their inability to communicate, which he finds exasperating and chides: If you’re unable to communicate, the least you can do is shut up about it. This also seems like sound advice for those who don’t really know what they’re talking about—but keep on talking anyway.

Dream On

In the highly entertaining book How to Be Good by Nick Hornby, one of the main characters writes a column called The Last Angry Man. I wish I were the last angry teacher—I really do—but until we can agree on the basics of reading instruction—and I mean those non-negotiables we now know so well—lots of teachers will remain angry on behalf of the students they serve. And so they should be.

Here’s the great idea I’m dreaming of:

I have a dream that one day education professors will not be judged by the content of their course materials but by their commitment to change coursework as the research dictates.

Clinging to pet theories and passing them on to teachers with unwavering conviction displays an alarming level of hubris that harms children. I have sat through Balanced Literacy trainings related to both reading and writing where I was knowledgeable enough in both subjects to quickly suss out the gaslighting. When teachers are told to second guess their own skepticism and emerging self-doubt about adopting instructional approaches thrust upon them that they know are leaving too many children behind, that’s not okay.

Reading methods that ignore the instructional implications of orthographic mapping serve the stories of yesteryear, not students. Stop the stories. Stop gaslighting teachers.

Always striving to make sense—please let me know when I fail.

Terrific piece!

The word gaslighting really stood out to me here, especially because it reflects something I’ve felt in recent conversations—when I’ve shared my experience reading with children and emphasized how decoding first before using context is what helps them most, I’ve sometimes been met with dismissal from folks not in classrooms every day. It’s frustrating, because like you said, if we could just say yes to this, we could go so much further, so much faster.

In my experience, many teachers who identify with balanced literacy already agree with this shift. They might not be loud on social media about it, but they’re making the change in their classrooms—often not because of a citation but because they see it works. It’s not a big leap for most of them; in fact, it’s often a relief. It makes teaching easier, and students move faster in their reading development.

Many still say they’re balanced literacy teachers, because much of what they’ve learned still holds value. But this shift—starting with decoding—has made all the difference.

I’ll keep doing my part by starting with this one big thing in the work I do with teachers and leaders. And I’ll keep sending folks to your Substack—because I agree, if we can get this shared understanding in place, we can move forward to the more nuanced conversations that truly need our attention.