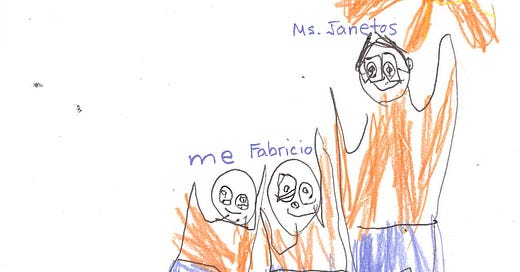

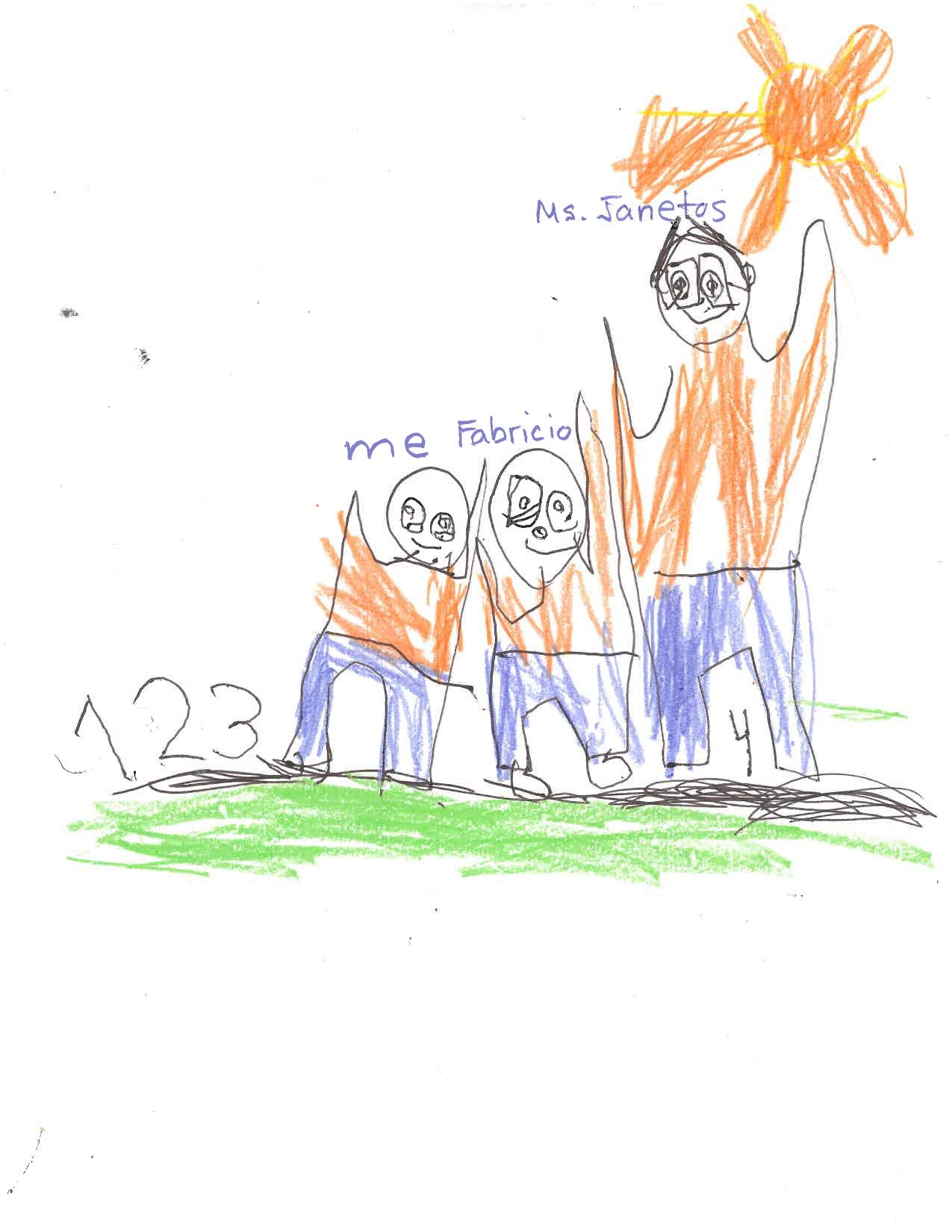

Here I am with the twins, Renzo and Fabricio—always trying our best to coordinate outfits. They were two of the many reasons why I loved my unexpected year teaching reading and writing in kindergarten, a year where I learned everything I needed to know about their favorite subject, Spider-Man—as well as mine: reading instruction.

I was both blessed and cursed to find myself in a completely empty classroom: no worksheets in filing cabinets to distract students with countless cutting and pasting activities; no teacher training in classroom decor to distract me from lesson planning. So what was in my teaching arsenal? I brought with me a reading specialist credential; training in the speech-to-print program Phono-Graphix (based on the work of cognitive psychologist Diane McGuinness); four years’ experience working with upper elementary struggling readers; and Stanislas Dehaene’s book Reading in the Brain. As it turned out, these resources—along with a set of white boards, decodable books, writing journals, and consumable booklets from the district’s ELA program—were all I needed.

Integrating Literacy Components

Because this was half-day kindergarten with only 80 minutes available for reading and writing instruction, I had to rely on instructional simultaneity long before the term appeared in the Handbook on the Science of Early Literacy (2023). Specifically, I combined my phonemic awareness (PA) instruction with my phonics instruction, which had been recommended two decades earlier in Diane McGuinness’s book Early Reading Instruction: What Science Really Tells Us about How to Teach Reading (2004).

According to McGuinness, there are a few basic elements of a successful beginning reading/spelling program, which she labels a Prototype for Teaching the English Alphabet Code. I’ve listed the elements of this prototype below. In the parentheses following each one, I’ve noted one or more researchers/educators whose publications over the past two decades have aligned in various ways (if not completely) with these recommendations.

Note in the first bullet point that what Diane McGuinness is referring to as sight words are high-frequency words that are memorized as a whole—not words that become recognized by sight after they have been orthographically mapped by connecting phonology, orthography, and semantics (sounds, spellings, and meaning)—which include all words, not just those that are high-frequency. (Bolded words were originally italicized in the book for emphasis.)

No sight words (except high-frequency words with rare spellings). (Linnea Ehri)

No letter names. (Stanislas Dehaene)

Sound-to-print orientation. Phonemes, not letters, are the basis for the code. (Richard Gentry and Gene Ouellette)

Teach phonemes only and no other sound units. (Susan Brady)

Begin with an artificial transparent alphabet or basic code: a one-to-one correspondence between 40 phonemes and their most common spelling. (David Share)

Teach children to identify and sequence sounds in real words by segmenting and blending, using letters. (Susan Brady)

Teach children how to write each letter. Integrate writing into every lesson. (Steve Graham)

Link writing, spelling and reading to ensure children learn that the alphabet is a code, and that the code works in both directions: encoding/decoding. (Linnea Ehri)

Spelling should be accurate or, at a minimum, phonetically accurate (all things within reason). (Gene Ouellette and Monique Sénéchal)

Lessons should move on to include the advanced spelling code. (Louisa Moats)

Note in particular:

Teach children to identify and sequence sounds in real words by segmenting and blending, using letters.

The Wonders of Word Building

This integration of phonemic awareness with letters was the focus of a word building intervention study: Focusing Attention on Decoding for Children with Poor Reading Skills: Design and Preliminary Tests of the Word Building Intervention by McCandliss, Beck, Sandak, Perfetti (2003). From the abstract:

The intervention directed attention to each grapheme position within a word through a procedure of progressive minimal pairing of words that differed by one grapheme. Relative to children randomly assigned to a control group, children assigned to the intervention condition demonstrated significantly greater improvements in decoding attempts at all grapheme positions and also demonstrated significantly greater improvements in standardized measures of decoding, reading comprehension, and phonological awareness.

I discovered this research right before my kindergarten assignment and immediately got a copy of Making Sense of Phonics: The Hows and Whys by Isabel Beck, one of the co-authors of the study. The book has lists of words with minimal pairing (shifting by one grapheme at a time: cat, cap, tap, map, mat) to guide my students in making word chains that simultaneously develop phonemic awareness and knowledge of letter sounds and patterns (a union of phonology and orthography), thereby maximizing my instructional time for foundational skills and leaving more time for other literacy components.

So when an oral-only PA program became popular in my district several years ago, ignoring it was easy, having achieved success (as well as saving time) teaching PA with letters. Then, more recently, I was thrilled to discover validation for this integration of PA with letters from Florina Erbeli and Marianne Rice (2025 co-recipient of the Rebecca L. Sandak Young Investigator Award presented by the Society for the Scientific Study of Reading) in A Meta-Analysis on the Optimal Cumulative Dosage of Early Phonemic Awareness Instruction (2024). Discussing their research on The Teaching Literacy Podcast, Erbeli and Rice emphasize that both PA with and without letters improved phonemic awareness—but it was PA with letters that improved reading and spelling.

I was surprised, therefore, to discover recently that the findings of this meta-analysis are not addressed in the monograph Teaching Phonemic Awareness in 2024: A Guide for Educators, which was published eight months after the Erbeli and Rice research came out. The authors of the PA guide declare:

Individual researchers occasionally put forward new claims and ideas, which should then be tested scientifically and clinically. Teaching practice should shift in response to new evidence, but it should not shift in response to new ideas proposed without ample new evidence from rigorous studies. Recently, a few academics have proposed that struggling readers do not benefit from phonemic awareness instruction beyond blending and segmenting and that oral phonemic awareness activities should not be a universal component of reading instruction in K-1. Yet over 40 years of research demonstrates how appropriate, systematic, and primarily oral phonemic awareness instruction benefits learning to read. Until there is new data from peer-reviewed studies indicating more benefit from an alternative method, educational practice should continue to align with existing scientific research on reading.

In fact, the stated concerns in the guide related to phonemic awareness instruction with letters are problematic because they undermine the importance of integrating PA with phonics in order to facilitate orthographic mapping and improve reading and spelling outcomes.

I’m listing these concerns, bolding what I see as problem areas, and following these statements with some comments based on my classroom experiences.

My goal: To make instruction both efficient and effective to improve reading outcomes, not just phonemic awareness outcomes.

Here are some specific points the authors make:

When teaching phonemic awareness with letters, each practice word must be spellable by all children in the group. Avoid spoken words with letter patterns that have yet to be learned.

Note: If we integrate PA with phonics, we can use segmenting and blending activities to teach new spelling patterns representing sounds. The activities themselves provide the practice in order for these “letter patterns” to be “learned” so they eventually become spellable by all children.

Some spoken words will be difficult for novice readers to represent with letters. For example, the same long A sound is spelled with different letters in “cake,” “paid,” “may,” “steak,” “hey,” and “weigh.”

Note: That’s the whole point! We are teaching spelling patterns and the sounds they represent. Dictated word chains with pay, paid, raid, rain, ray, may, main practice PA and phonics together, especially if we are asking students to say the sound (phoneme) as they write the letter or pattern (grapheme).

If using letters in a phonemic-awareness-style task, teachers must decide whether the child who segments “paid” into /p/ /a/ /d/ and chooses the letters p-a-d has given a correct answer or an incorrect answer, when the goal of the activity is to build phonemic awareness.

Note: This is a great example of the importance of efficiency. It is more efficient to combine PA with phonics to give students the opportunity to learn and practice spelling patterns. The goal is to help students become better readers, and building phonemic awareness is a byproduct—not the goal—of the activity.

When letters are used in phonemic-awareness-style tasks, letter identification errors and letter reversals can interfere with learning the phonemic awareness task.

Note: Once again, is the goal to learn a phonemic awareness task or to become a better reader? If both PA with and without letters improve phonemic awareness, but PA with letters also improves spelling and reading, isn’t PA with letters the more efficient choice?

If letters are always used during phonemic awareness instruction, then phonemic awareness instruction becomes indistinguishable from spelling regular words.

Note: Why is this such a bad thing if using letters during phonemic awareness instruction leads to better reading outcomes? And since we know that orthographic mapping requires linking phonology with orthography, then uniting PA with letters promotes orthographic mapping.

One of the main reasons to begin phonemic awareness instruction is to facilitate learning for students who are struggling with learning phonics and spelling words as they sound. Such students are likely to know fewer letter-sound correspondences, so using letters instead of tokens in phonemic awareness tasks can limit the number of items for practice.

Note: If students are shown the letters on the board and/or have letter tiles to manipulate, they can learn letter-sound correspondences as they practice PA.

Using letters can confuse the interpretation of student errors. If a student responds incorrectly to a phonemic task using letters, it is difficult to know whether the error is due to poor phonemic awareness or inadequate letter-sound knowledge.

Note: If a child makes/writes the word ‘brain’ as ‘bain’, it’s a PA problem. If they make/write the word ‘brain’ as ‘brayn’, it’s a phonics problem. And if they make/write it as ‘bayn’, it’s both.

The Chicken-Egg Problem

In Becoming Phonemic Mark Seidenberg introduces the chicken-egg problem:

‘Phonemic awareness’ isn’t the prerequisite to reading. It develops in conjunction with learning about print. The Important Idea: ‘Phonemic awareness’ is both necessary for reading alphabetic writing and a product of reading alphabetic writing. How can this be? Chicken-egg problem! The Answer: Learning is interactive, reciprocal, interdependent. Learning one thing influences learning another—and vice versa. The opposite of: learn phonemes, then print, then phonics.

This chicken-egg problem reminds me of the old joke:

Doctor, my wife thinks she’s a chicken. I didn’t do anything about it before because we really needed the eggs.

Similarly, I think I can teach phonemic awareness with letters—in fact, I’m convinced I can—and I’m sticking with this practice because I really need the reading results as well as the extra time I gain to address other literacy components.

Researchers sparring over their preferred studies has become a spectator sport for teachers in this era of the science of reading movement, where it’s easy to become hyper-focused on each and every recommendation: an abundance of advice amidst a dearth of decision-making guidelines. In a recent post, When Conversations Get Hard: Finding Common Ground in the Literacy World, literacy coach Leah Mermelstein gives some practical suggestions for teachers, including:

Strong conversations aren’t about having all the answers. They’re about being curious about what someone else can offer.

And in the International Dyslexia Association’s 75th anniversary issue, Reid Lyon and Margaret Goldberg observe:

Science is open-minded and objective. It doesn’t take sides but rather illuminates a path. If new data confront and overturn long-held assumptions and beliefs, even about Structured Literacy, we need to make changes that reflect this new information, not succumb to confirmation bias.

Teachers rooting for researchers isn’t appropriate in this reading instruction game we’re watching from the stands since science doesn’t choose sides—it chooses data—so we must simply side with the science. This means we are left doing our best to choose effective methods that are also efficient ones—which buys us time to teach all the other stuff besides reading. And if we somehow manage to pull this off, we can call it a day—and a win for our students.

Always striving to make sense—please let me know when I fail.

Harriett, you are brilliant in how you synthesize information for us to easily understand. Thank you for your time and talent on this piece.

The weariness of the reading wars is real. And the data you just provided is the exact kind of data is needed to inform the research. If there weren’t some validity in the “sides,” there wouldn’t be a war to fight. Your critical appraisal of what is being asked of you to replace what you have already found successful - that’s the kind of wisdom that is too often missing from the conversation. Thank you for raising your voice!